Emmanuelle Charpentier

"I have always been encouraged by my parents to explore my own academic interests. Although it was not clear at the time that I would eventually study biology, I showed an interest in science very early on. In fact, I was interested not only in pure sciences and mathematics, but also in the human sciences — psychology, sociology and philosophy."

Microbiologist Emmanuelle Charpentier and biochemist Jennifer Doudna co-invented the gene-editing system CRISPR-Cas9, a versatile technology for editing DNA on an unprecedented scale with extremely high precision.

Born in Juvisy-sur-Orge, France, Charpentier was interested in sciences from a young age. “I have always been encouraged by my parents to explore my own academic interests,” she said. “Although it was not clear at the time that I would eventually study biology, I showed an interest in science very early on. In fact, I was interested not only in pure sciences and mathematics, but also in the human sciences — psychology, sociology and philosophy.”

Charpentier studied biochemistry, microbiology and genetics at the University Pierre and Marie Curie (now Sorbonne University) in Paris, and obtained her doctorate in microbiology for her research performed at the Pasteur Institute in Paris.

By the time Charpentier and Doudna met in 2011 at a scientific conference, both had already been researching different aspects of CRISPR, an immune system used by bacteria to fend off viruses — Charpentier at Umeå University in Sweden, and Doudna at the University of California, Berkeley.

Doudna was focused on RNA, a partner to DNA in carrying genetic information, and was researching how a repeating sequence of DNA in the bacterial genome enabled bacteria to fight viral infections. Charpentier had published findings about an unusual RNA called tracrRNA, and how it works with the Cas (CRISPR-associated) 9 protein in RNA processing that contributes to the identification and elimination of invading viruses. Their collaboration yielded a leap in innovation.

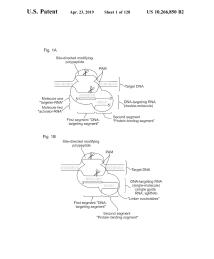

While collaborating, the Charpentier and Doudna labs discovered how Cas9 is guided by both the tracrRNA and an RNA matching a target sequence, using it to find and cut matching target DNA. They also engineered the two RNAs into different formats, such as truncated versions and a simplified single guide RNA format. They showed that the RNAs could be designed to pinpoint any gene, allowing the Cas9 protein to cut at that spot. Charpentier and Doudna correctly foresaw considerable exploitation of this easily programmable system for gene targeting and gene editing applications in all forms of life.

CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology has since been widely applied across scientific fields including human and veterinary medicine, agriculture and biotechnology. It has been rapidly adopted by the scientific community due to its broad applicability, versatility and ease of use.

“The field of CRISPR-Cas9 continues to develop at dazzling speed, with exciting new developments emerging almost weekly,” said Charpentier, who holds more than 50 U.S. patents.

In 2015, Charpentier joined the Max Planck Society and since 2018, she is director of the Max Planck Unit for the Science of Pathogens. She is also the co-founder of CRISPR Therapeutics and ERS Genomics together with Rodger Novak and Shaun Foy.

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Charpentier and Doudna in 2020. Among their many additional honors are the Kavli Prize in Nanoscience and the Wolf Prize in Medicine.