Ching Wan Tang

"What’s most important is that you always experiment with ideas. That’s the key to all inventions. You also have to be persistent. You experiment, and you observe, and hopefully you will discover something new and useful."

Chemists Ching Wan Tang and Steven Van Slyke pioneered the organic light emitting diode, or OLED. An advance in flat panel displays found in computers, cellphones and televisions, the OLED provides increased power efficiency, longer battery life and improved display quality.

Born in Yuen Long, Hong Kong, in 1947, Tang grew up in a small community of just 12 families, where he worked in rice fields. At a young age, he developed what might have been his very first invention – a makeshift raking tool made of scrap wood and nails, which made weeding in wet rice fields more efficient.

After graduating from high school, Tang moved first to Canada, where he earned his bachelor’s degree in science from the University of British Columbia in 1970, and then to the U.S., earning his doctorate in chemistry at Cornell University in 1975. Also in 1975, Tang accepted a position at Eastman Kodak Co. as a research scientist, where he was assigned to work on organic solar cells.

While at Eastman Kodak, Tang hired Van Slyke as his research assistant. Having realized that organic materials could efficiently convert electricity into light, the pair applied the organic heterojunction – a bilayer structure of an electron donor and an electron acceptor invented by Tang – to various applications including OLEDs.

“What’s most important is that you always experiment with ideas,” Tang said as he reflected on his work in an interview with the National Inventors Hall of Fame®. “That’s the key to all inventions. You also have to be persistent. You experiment, and you observe, and hopefully you will discover something new and useful.”

Tang and Van Slyke relied on Kodak’s chemical library, where thousands of chemicals had been collected since the 1940s. Here, they found a metal chelate that produced a lasting glow. “Finding the chelate, the compound, was truly a turning point,” Tang said. “That was the beginning of the practical OLED.”

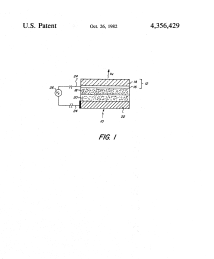

OLEDs, which consist of thin films sandwiched between two electrodes, can be used wherever liquid crystal displays (LCDs) are used. They are thinner, lighter and more efficient, provide superior brightness and color, and offer ultra-fast response time for functions such as refreshing and on-off switching. Unlike LCDs that rely on a backlight that passes through color filters to produce light, OLED screens use luminescent organic materials to make their own light. Because they are flexible, OLEDs also have made it possible to create curved screens.

The first OLED product was a display for a car stereo, commercialized by Pioneer in 1997. In 2003, Kodak introduced the EasyShare LS633 digital camera, which became the first consumer electronic product to incorporate a full-color OLED display. The first television featuring an OLED display, produced by Sony, entered the market in 2008. Today, OLEDs are used in an array of products, including smartphones and smart wearable devices, tablets, TVs, virtual reality headsets, digital signs and vehicle displays. By 2034, the global OLED display market is expected to grow to more than $344 billion.

After 31 years at Kodak, Tang retired as Distinguished Fellow of the Kodak Research Laboratories in 2006. Continuing his passion for learning and discovery, he subsequently joined the University of Rochester as the Doris Johns Cherry Professor of Chemical Engineering, and in 2013, he was appointed as the IAS Bank of East Asia Professor of the Jockey Club Institute for Advanced Study at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Named on more than 80 patents, Tang has received numerous awards for his work on organic materials and electronics, including the 2004 American Chemical Society Award for Team Innovation, an honor he shares with Van Slyke, and the 2011 Wolf Prize in Chemistry. “Usually, you don’t discover something that’s totally unexpected,” said Tang. “You must be thinking about the problem all the time, even in your sleep. You just try mentally, one way or another, or in the lab, one way or another, and you keep thinking about it. And somehow, the door cracks open, and that’s discovery.”